Thursday, July 12, 2007

Human Rights Watch (HRW ) News

From Human Rights Watch

Call Your Senator – Stop US Funding of Child Soldiers

National Phone-In Day, JULY 12, 2007

SUPPORT THE CHILD SOLDIER PREVENTION ACT OF 2007 (S. 1175)

Restrict US Military Assistance to Governments Using Child Soldiers

On July 12, please take a moment to phone and ask your senator to support S. 1175, the Child Soldier Prevention Act of 2007. This important legislation would restrict US military financing, training and arms transfers to governments that are involved in the recruitment and use of child soldiers.

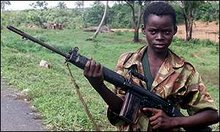

Of nine governments worldwide implicated in the recruitment or use of children as soldiers, eight currently receive US military assistance. US tax dollars should not be used to support the exploitation of children as soldiers. US weapons should not end up in the hands of children.

The Child Soldier Prevention Act was introduced by Senators Richard Durbin (D-IL) and Sam Brownback (R-KS), and is already co-sponsored by over a dozen other US senators, including both Republicans and Democrats. We need additional co-sponsors to get the bill passed.

Please Call Your Senators on July 12.

Sample message:

“My name is ____, and I’m calling from (town/city, state). I’m very concerned about the recruitment and use of child soldiers around the world. I am calling because I would like the senator to co-sponsor S. 1175, the Child Soldier Prevention Act. I believe this bill can make a difference in ending the use of

child soldiers, and believe it deserves the Senator’s support.”

Calls to senate offices are usually taken by receptionists who briefly note the topic you are calling on. You will not be asked for detailed information.

Find your senators’ phone numbers at: www.senate.gov

Senators who have already co-sponsored the bill (as of July 2, 2007):

Bingaman (D-NM), Boxer (D-CA), Brownback (R-KS), Casey (D-PA), Coburn (R-OK), Cochran (R-MS), Durbin (D-IL), Feingold (D-WI), Feinstein (D-CA), Johnson (D-SD), Kerry (D-MA), Menendez (D-NJ), Mikulski (D-MD), Reed (D-RI), Roberts (R-KS), Snow (R-ME).

We particularly encourage calls to members of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee who have not yet co-sponsored the bill:

Benjamin Cardin (D-MD) (202) 224-4524

Norm Coleman (R-MN) (202) 224-5641

Bob Corker (R-TN) (202) 224-3344

Jim DeMint (R-SC) (202) 224-6121

Christopher Dodd (D-CT) (202) 224-2823

Chuck Hagel (R-NE) (202) 224-4224

Johnny Isakson (R-GA) (202) 224-3643

Lisa Murkowski (R-AK) (202) 224-6665

Bill Nelson (D-FL) (202) 224-5274

Barack Obama (D-IL) (202) 224-2854

John Sununu (R-NH) (202) 224-2841

David Vitter (R-LA) (202) 224-4623

George Voinovich (R-OH) (202) 224-3353

Jim Webb (D-VA) (202) 224-4024

Thank you for your time.

Your call WILL make a difference.

Call Your Senator – Stop US Funding of Child Soldiers

National Phone-In Day, JULY 12, 2007

SUPPORT THE CHILD SOLDIER PREVENTION ACT OF 2007 (S. 1175)

Restrict US Military Assistance to Governments Using Child Soldiers

On July 12, please take a moment to phone and ask your senator to support S. 1175, the Child Soldier Prevention Act of 2007. This important legislation would restrict US military financing, training and arms transfers to governments that are involved in the recruitment and use of child soldiers.

Of nine governments worldwide implicated in the recruitment or use of children as soldiers, eight currently receive US military assistance. US tax dollars should not be used to support the exploitation of children as soldiers. US weapons should not end up in the hands of children.

The Child Soldier Prevention Act was introduced by Senators Richard Durbin (D-IL) and Sam Brownback (R-KS), and is already co-sponsored by over a dozen other US senators, including both Republicans and Democrats. We need additional co-sponsors to get the bill passed.

Please Call Your Senators on July 12.

Sample message:

“My name is ____, and I’m calling from (town/city, state). I’m very concerned about the recruitment and use of child soldiers around the world. I am calling because I would like the senator to co-sponsor S. 1175, the Child Soldier Prevention Act. I believe this bill can make a difference in ending the use of

child soldiers, and believe it deserves the Senator’s support.”

Calls to senate offices are usually taken by receptionists who briefly note the topic you are calling on. You will not be asked for detailed information.

Find your senators’ phone numbers at: www.senate.gov

Senators who have already co-sponsored the bill (as of July 2, 2007):

Bingaman (D-NM), Boxer (D-CA), Brownback (R-KS), Casey (D-PA), Coburn (R-OK), Cochran (R-MS), Durbin (D-IL), Feingold (D-WI), Feinstein (D-CA), Johnson (D-SD), Kerry (D-MA), Menendez (D-NJ), Mikulski (D-MD), Reed (D-RI), Roberts (R-KS), Snow (R-ME).

We particularly encourage calls to members of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee who have not yet co-sponsored the bill:

Benjamin Cardin (D-MD) (202) 224-4524

Norm Coleman (R-MN) (202) 224-5641

Bob Corker (R-TN) (202) 224-3344

Jim DeMint (R-SC) (202) 224-6121

Christopher Dodd (D-CT) (202) 224-2823

Chuck Hagel (R-NE) (202) 224-4224

Johnny Isakson (R-GA) (202) 224-3643

Lisa Murkowski (R-AK) (202) 224-6665

Bill Nelson (D-FL) (202) 224-5274

Barack Obama (D-IL) (202) 224-2854

John Sununu (R-NH) (202) 224-2841

David Vitter (R-LA) (202) 224-4623

George Voinovich (R-OH) (202) 224-3353

Jim Webb (D-VA) (202) 224-4024

Thank you for your time.

Your call WILL make a difference.

Sunday, July 8, 2007

Former chld soldier - Salifou Yankene

From New York Times May 13, 2007

The teenager stepped off an airplane at Kennedy International Airport on Nov. 8 and asked for asylum. Days before, he had been wielding an automatic weapon as a child soldier in Ivory Coast. Now he had only his name, Salifou Yankene, and a phrase in halting English: “I want to make refugee.”

Lawyers for Salifou, Elliot F. Kaye and Rachel B. Kane, went to the International Rescue Committee office in Manhattan to seek help for him. More Photos »

Eventually Salifou’s story would emerge, and in granting him asylum, one of the system’s toughest judges would find it credible: the assassination of his father and older sister when he was 12; the family’s flight to a makeshift camp for the displaced; his conscription at 15 by rebel troops who chopped off his younger brother’s hand; and an extraordinary escape two years later, when his mother risked her life to try to save him.

But when a lawyer took the case without fee in January, Salifou, then 17, was almost ready to give up. Detained in a New Jersey jail, overtaken by guilt, anger and despair, he resisted painful questions, sometimes crying, “Send me back!” And the lawyer soon realized that saving Salifou would require much more than winning him asylum.

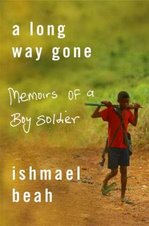

There are 300,000 child soldiers worldwide, human rights groups say. Only a few have ever made it to the United States, but campaigns to halt recruitment and rehabilitate survivors are resonating here — not least because a best-selling memoir by one former child soldier, Ishmael Beah, has put a compelling human face on the potential for redemption.

Yet no one has really grappled with how to handle those who make it to this country seeking refuge.

Their violent pasts pose hard questions: Should they be legally barred from asylum as persecutors or protected as victims? How can they be healed, and who will help them?

Both Salifou and Mr. Beah, who testified on Salifou’s behalf, show that on the ground, the answers are haphazard, and the results may turn on the kindness of strangers.

Mr. Beah, now a 26-year-old who exudes a gentle radiance, surged to celebrity with “Long Way Gone,” showcased at Starbucks and acclaimed on “The Daily Show.” The book tells how he was orphaned, drugged up, indoctrinated and made to kill indiscriminately by government forces in Sierra Leone’s civil war — and then reclaimed by counselors at a Unicef rehabilitation center.

But unlike Mr. Beah, who became a permanent resident without applying for asylum, Salifou has faced legal opposition from the government. And while Mr. Beah has had a decade to adjust to America, go to college and come to terms with his past, Salifou’s story is still raw, and changing.

Less than three weeks ago, days after his 18th birthday, immigration authorities abruptly released Salifou alone, at 10 p.m., on a street corner in Lower Manhattan.

“They say, ‘You free to go,’ ” he recalled, eyes wide. “I say, ‘Go where?’ ”

That night, the former child soldier — now over six feet tall, with toned muscles and a diagnosis of severe post-traumatic stress disorder — slept on a couch in the Brooklyn apartment of his lawyer, Elliot F. Kaye, near the toy trains of Mr. Kaye’s 2-year-old son.

Salifou could still be deported. At his asylum hearing in April, the government argued that based solely on his own account, he was a persecutor, and thus legally barred from refuge.

When the judge disagreed, citing Salifou’s youth and coercion by his rebel captors, a government lawyer invoked a right to appeal that will not expire until May 23.

Ernestine Fobbs, a spokeswoman for Immigration and Customs Enforcement, said on Friday that the agency did not comment on active cases.

Salifou testified that to satisfy leaders who punished disobedience with death, he had looted during raids, grabbed new child conscripts and hit and kicked civilians without pity if they resisted. He maintained, though, that while he had shot at people, he had never knowingly killed anyone.

Many mysteries remain in the story of the escape of this adolescent, whose sheltered, upper-middle-class childhood and French schooling in West Africa ended abruptly with his father’s murder.

One is the real identity of the foreigner his mother called Father William, who smuggled him onto a plane to Geneva, he said, outfitted him in jeans and Timberland boots, and sent him on to New York with a false Swiss passport.

Were Salifou deported now, concluded the judge in the case, Alan L. Page — who has denied 83 percent of asylum cases brought before him — he could face jail, torture or death from both sides in the conflict dividing Ivory Coast.

Instead, on Salifou’s first day of freedom, he awoke in the Kayes’ small Cobble Hill apartment, with the French books he had collected in jail: math and physics texts, Harry Potter paperbacks and a short story by Balzac that had made him cry, he said, because, like Mr. Beah’s testimony, “it is my own history.”

When the lawyer took Salifou’s case last winter, Mr. Beah’s memoir had not yet been published, but an adaptation in The New York Times Magazine led Mr. Kaye to contact Laura Simms, the woman Mr. Beah calls his second mother.

“How did you do that?” Mr. Kaye said he asked her, when he learned that she had taken Mr. Beah into her home as soon as he arrived on a hard-won temporary visa in 1998. “I remember saying: ‘I have a wife and a young son. He may not even know how dangerous he still is.’ ”

Ms. Simms became his mentor, the guide to an expanding circle of strangers determined to rescue Salifou — even, if necessary, from himself.

“At first I distrusted everyone,” Salifou said in French. “Elliot said, ‘Life is giving you a second chance.’ All I wanted was death.”

“Little by little, Elliot changed that.”

Unlike Mr. Beah, who had major trauma therapy in his country in a residential center staffed by trained counselors, Salifou was facing his demons in an adult jail, and the lawyers probing for details of his life, against asylum deadlines, were in effect his only therapists.

Sometimes, the lawyers said, they found a petulant teenager, or an angry soldier; sometimes he was a child closing his eyes, longing to be magically transported back to a time when his family was intact and pillow fights were his only combat.

“We realized we had to make him remember things that he wanted desperately to forget,” said Bryan Lonegan, the Legal Aid lawyer who screened Salifou’s case at the Sussex County, N. J., jail and enlisted the help of Mr. Kaye and his colleagues at the Cooley Godward Kronish law firm in Manhattan.

By then, Salifou had good reason to be confused and distrustful of the system he had entered when he sought asylum. Like many of the 5,000 unaccompanied minors apprehended each year, he had no valid identity documents. But based on the birth date he gave, he had been placed in a juvenile shelter in Queens.

Within days, after confiding to a counselor that he sometimes heard voices and had once attempted suicide, he was transferred to a mental hospital’s pediatric ward, where he was so medicated, he said, that he could barely move.

Discharged in time for Thanksgiving dinner at the children’s residence, he was suddenly declared to be over 18, not 17 years and 7 months as he maintained, based on an immigration service dentist’s interpretation of his X-rays — a practice that many doctors contest as unreliable. An adult immigration detention center refused to take him, so he was locked up in a county jail in western New Jersey.

His experience evokes the larger international confusion over how to draw the line between juveniles and adults, and what treatment is best for former child soldiers.

In one sense, Salifou’s childhood ended on Aug. 6, 2001, according to the 25-page affidavit he signed. That was the day his father and older sister were shot to death within earshot of the family home in Man, a market town in northwestern Ivory Coast. He remains tormented that as a 12-year-old he was powerless to protect his family when armed men ransacked the house and assaulted his mother.

His father, a civil servant in the defense ministry, had been politically active with an opposition party, but may also have dealt in arms and diamonds. He had been able to afford to send Salifou to a French school, where he excelled.

But after the murders of his father and sister, he fled with his mother, brother and two younger sisters. For three years, they lived in a roving camp for the displaced, and it was all they could do to stay alive.

Late in 2004, troops of the Mouvement Patriotique, the rebel faction that controlled the north, raided the camp for new recruits. As rebels grabbed Salifou and his younger brother, Abdul Razack, then about 13, their mother held on to Abdul’s arm, yelling that he was too young to take. To punish her, Salifou testified, one rebel chopped off Abdul’s hand with a machete.

Abdul was left behind, but Salifou was thrown in the back of a truck with other boys and began two years as an unwilling child soldier among thousands — trained, armed, drugged and growing numb to violence.

“There are some who can’t be healed anymore,” he said two days after his release, confessing that firing a machine gun had seemed “cool,” the power, heady. “There are some who can’t stop killing and giving orders. There are people who hate people. If you had a terrible childhood, if you hated your parents ...” He added, “I loved my parents.”

In the end, he said, his mother helped him persuade his chief to let him visit her briefly after one of his raids stumbled on her village camp again. Later, with a well-timed gift of a yam for his leader, she had Salifou return and meet Father William, a friend of his father’s who would take him to safety.

“I told her that I wasn’t going to leave,” he said, mindful that the rebels often hurt or killed the families of those who escaped. “But she forced me.”

He has had no contact with his family since. The lawyers, despite tantalizing near-misses, failed to locate Father William, who drove Salifou to the capital, Abidjan, dressed him as a luggage handler to get him past airport security, then guided him onto an airplane to Geneva. There, Salifou said, he gave him a passport and instructions for a flight to the United States.

Salifou arrived in November knowing no one. Now his circle of supporters includes the lawyers who took him on a giddy shopping spree for sneakers, T-shirts and a Yankees cap the day after his release on April 23. It includes Ms. Simms, who saw his descent into deep sorrow the next day, twisting his fingers and saying he just wanted to sit in the dark.

A few days later, Salifou seemed resilient, even joyful, after a session with a therapist at Bellevue Hospital, prayer at the 96th Street mosque and a dinner cooked by Mr. Beah in Ms. Simms’s homey kitchen.

“A family was born,” said Salifou, who is now staying in Harlem with an interpreter who is himself an African refugee. “It’s true what I was taught, what the philosopher said: Nothing is lost, nothing is created, everything is transformed. I thought I lost a family, but it was transformed.”

It was a lesson from physics, applied to humankind, and Mr. Beah, the writer, echoed the sentiment.

“I realized what an intelligent, calm and sweet person he is,” he said. “He just happened to have the misfortune of having his childhood taken from him. But you can see him coming back.”

“I consider him like a brother to me,” he added, “because we’re both coming from a place where we have learned to deeply understand the true nature of violence, what war really is and what it does to the human spirit.”

Friday, July 6, 2007

International Labor Organization (ILO)

In 1999 the International Labor Organization (ILO) was called upon to boost efforts to end children’s participation in armed conflicts around the world. The convention defines the recruitment of children for use in armed conflict as the worst form of child labor. Now ratified by 156 International Labor Organization (ILO) member states, the convention calls for the urgent elimination of these practices.

Child soldiers share many challenges with both adult combatants and non-combatant children. But they also face unique difficulties. These stem from the evolution of weapons and warfare; the breakdown of law and order in conflicts; intolerable levels of poverty, unemployment, inequality, and social exclusion; weak educational and training structures; rampant violence and abuse; and social pressures to engage in armed conflicts, other dangerous labor, or harmful activities like drug use.

ILO seeks to overcome these difficulties and promote the long-term reintegration of child soldiers. Methods used to reintegrate former child soldiers include vocational training, apprenticeship programs, family support, stipends, psycho-social counseling, detoxification, capacity building of local institutions, and partnership development. ILO recognizes the need to consult child soldiers themselves in planning and implementing projects. With girls also commonly involved in conflicts, either as combatants or victims of exploitation, gender dimensions of socio-economic reintegration are crucial.

ILO - Reintegrating Child Soldiers

Child soldiers share many challenges with both adult combatants and non-combatant children. But they also face unique difficulties. These stem from the evolution of weapons and warfare; the breakdown of law and order in conflicts; intolerable levels of poverty, unemployment, inequality, and social exclusion; weak educational and training structures; rampant violence and abuse; and social pressures to engage in armed conflicts, other dangerous labor, or harmful activities like drug use.

ILO seeks to overcome these difficulties and promote the long-term reintegration of child soldiers. Methods used to reintegrate former child soldiers include vocational training, apprenticeship programs, family support, stipends, psycho-social counseling, detoxification, capacity building of local institutions, and partnership development. ILO recognizes the need to consult child soldiers themselves in planning and implementing projects. With girls also commonly involved in conflicts, either as combatants or victims of exploitation, gender dimensions of socio-economic reintegration are crucial.

ILO - Reintegrating Child Soldiers

Tuesday, June 12, 2007

Former child soldier -- Ishmael Beah

In 1991 when the Civil war in Sierra Leone reached it's height, Ishmael Beah's parents and two brothers were killed. At the age of 13, he was recruited by the government army as a child soldier. He fought nearly three years before being rescued by UNICEF. Shortly after the capital of Sierra Leone was over run by the RUF and the Sierra Leone army, Beah fled to the United States with the support of his foster mother, Laura Simms. In New York City, Beah attended the United Nations International School in Manhattan. After high school, he attended Oberlin College, graduating in 2004 with a degree in Politics.

During his time in the government army, Beah was forced to commit horrible atrocities which included the murder of several people. He and other soldiers smoked marijuana and sniffed amphetamines and a mixture of cocaine and gunpowder called "brown-brown". The influence of these drugs alowed Beah to commit countless acts of violence. The addictions, and the pressures of the army, made it impossible to leave on his own. "The only choice you had was to stay," Beah said. "If you left, it was as good as being dead."

During an appearance on The Daily Show on February 14, 2007, he said that he believed that returning to civilized society was more difficult than the act of becoming a child soldier—that dehumanizing children is a relatively easy task. Rescued in 1996 by a coalition of UNICEF and NGOs, he found the transition difficult. He and his fellow child soldiers fought frequently. He credits one volunteer, Nurse Esther, with having the patience and compassion required to bring him through the difficult period. She recognized his interest in American rap music, gave him a Walkman and a Run-D.M.C. cassette, and employed music as his bridge to his past, prior to the violence. Slowly, he accepted her assurances that "it's not your fault."

"If I choose to feel guilty for what I have done, I will want to be dead myself," Beah said. "I live knowing that I have been given a second life, and I just try to have fun, and be happy and live it the best I can.

While at college at Oberlin, Beah pursued advocacy work against the abuse of children in wartime. He spoke at the UN and met with world leaders including Bill Clinton and Nelson Mandela.

He currently works for Human Rights Watch Children’s Division Advisory Committee, lives in Brooklyn, and is considering attending graduate school.

Click Here to view video

Thursday, June 7, 2007

In 2002, Béoué's life changed drastically when war broke out in Côte d'Ivoire and an armed rebellion split the nation in two, drawing in warlords and fighters from neighbouring Liberia and Sierra Leone. Béoué's village was attacked and burned.

Those who were fit enough managed to escape and hide in the bush. Béoué, who was 13 at the time, decided he wanted to join the fighting forces. He felt he had nothing to lose, since most of his relatives had been killed in the attack.

Reintegrating Béoué required that he learn a trade to make a place in his community. With the assistance of UNICEF and the European Commission’s Humanitarian Aid Department (ECHO) he has learned construction skills. Due to his experience as an ex-combatant he is used to organizing activities and delegating responsibility and mastering his trade.

By Sacha Westerbeek

Click here to view video

For more information please visit http://www.unicef.org/emerg/cotedivoire_39645.html

Monday, June 4, 2007

Convention on the Rights of the Child

The Convention on the Rights of the Child sets out the rights that must be realized for children to develop their full potential, free from hunger and want, neglect and abuse. It reflects a new vision of the child. Children are neither the property of their parents nor are they helpless objects of charity. They are human beings and are the subject of their own rights. The Convention offers a vision of the child as an individual and as a member of a family and community, with rights and responsibilities appropriate to his or her age and stage of development. By recognizing children's rights in this way, the Convention firmly sets the focus on the whole child.

See a full list of the Rights of Children at the following link

www.unhchr.ch/html/menu3/b/k2crc.htm

See a full list of the Rights of Children at the following link

www.unhchr.ch/html/menu3/b/k2crc.htm

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

With an armed rebellion threatening to undermine Uganda’s progress to economic development, child soldiers emerge as central figures amid deadly violence and growing humanitarian emergency.

With an armed rebellion threatening to undermine Uganda’s progress to economic development, child soldiers emerge as central figures amid deadly violence and growing humanitarian emergency.